Among DORA’s more controversial findings is that trunk based development is superior to feature branching.

Teams achieve higher levels of software delivery and operational performance (delivery speed, stability, and availability) if they follow these practices:

- Have three or fewer active branches in the application’s code repository.

- Merge branches to trunk at least once a day.

- Don’t have code freezes and don’t have integration phases.

Since we know not to be Cremoninis, we won’t be distracted by whether trunk-based development meets the HN trendiness standard, and we’ll be skeptical of anectdotal appeals to experience

Still, why does trunk based development predict higher performing teams?

The Core Principle of CI

The core principle of Continuous Integration is that there should be “one interesting version”.

When we have multiple versions, spread across feature branches, we end up with “merge hell”.

Merge Hell Example

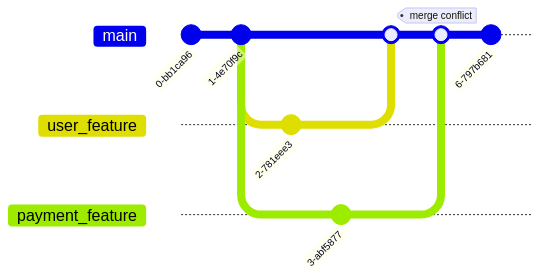

Consider a scenario where two developers are working on separate features for the same application. They each create a feature branch and spend a week developing their respective features. At the end of the week, they’re ready to merge their changes back into the main branch, or the ’trunk'.

However, because they’ve been working in isolation, their changes conflict with each other, causing bugs that weren’t present when the features were tested on their individual branches. This is ‘merge hell’, and it can significantly slow down the development process and reduce the overall quality of the software.

Trunk Based Development

Trunk-based development is a strategy designed to avoid this problem. In this approach, all developers work on a single branch, the ’trunk’.

They integrate their changes frequently, at least once a day, and these changes are immediately tested. This frequent integration and testing ensure that issues are caught and resolved early, reducing the risk of merge hell.

The most recent version of the trunk, assuming it has passed all tests, is considered the single “interesting” version of the application.

Microservices

Microservices are a means of implementing a loosely coupled architecture. This too is predictive of higher performing software organizations.

As we transition from a monolithic architecture to a microservices environment, the principles of trunk-based development remain relevant, but they take on a new dimension.

In a microservices architecture, each service is developed, deployed, and scaled independently. This independence is a strength.

However, the merge hell can re-emerge in even more painful form even if you practice trunk based development in your services.

Version Tetris

Consider the common scenario of an enterprise application implemented with a single SPA and a set of supporting backend services. The SPA makes calls to these services, either directly or through an abstraction later like GraphQL.

However, the changes to this service are not ready for end users yet. Either they haven’t been signed off by the QA team, or the end users need trainings before they can use the new features.

The reason doesn’t matter. What does? You start holding versions back.

Suppose you have a dev, staging, UAT, and production environment. A feature is completed in development and deployed to staging for QAs to review. However, production users certainly aren’t ready yet, and UAT users don’t want disruptions.

So you decide not to deploy the more recent version to UAT or production.

You start to end up with a situation that looks like this:

| Dev Version | Staging Version | UAT Version | Prod Version | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frontend SPA | v100 | v100 | v90 | v85 |

| Auth Service | v75 | v75 | v75 | v75 |

| Payments Service | v50 | v49 | v45 | v40 |

| Snazzy Feature Service | v60 | v57 | v53 | v50 |

No two environments are the same! Inter-service dependencies are bad enough. But typically your front end will depend on most (or all) of the backend services. Just because your front end works in staging, doesn’t mean it will work in UAT or production.

You don’t have one interesting version of your system, you have four. And they’re probably interesting in the wrong way.

But wait! It doesn’t stop there – the versions have dependencies on each other.

The frontend SPA will depend on various backend versions. For example, a change in payments on the frontend requires a change in the payments service on the backend.

Distributed Merge Hell

Now, you have the same problem as before, but much worse. We have recreated merge hell, and made it distributed.

Our new “merge” is trying to identify the set of versions we can deliver to end users.

Our new feature branches are the environments. The individual commits are the versions we bring into the environment.

Using versions to control features is feature branching on the service level.

Escaping Merge Hell

There’s only one way out. Versions should propagate to higher environments. You should have “one interesting version”.

But this brings us back to the need for continuous integration. To integrate is to bring something together into a whole. To do so continuously means to avoid batching the work.

The difficulty is this: to do this, you need a CI process that gives you confidence no regressions propagate to end users. That means an automated regression test suite you can depend on. It means contract testing to identify broken promises between services.

But the bad news is the good news. This is necessary anyway to delivery quality software. If the rush to continuous delivery forces improvements in the CI process, what are the down sides?